Matthew Hollett is a visual artist and writer in St. John’s, Newfoundland & Labrador. He makes books and other interactive works that investigate landscape and memory through photography, writing and walking. His work has most recently been published in Riddle Fence and Arc, and previously in anthologies such as The March Hare Anthology (Breakwater Books, 2007), and Shift & Switch: New Canadian Poetry (The Mercury Press, 2005). His creative non-fiction piece, “Comfort Zone,” was shortlisted for PRISM’s 2015 CNF Contest, and now appears in our current issue, Fall 55.1.

Read an excerpt from “Comfort Zone,” followed by an interview with PRISM Prose Editor, Christopher Evans, below.

I can recall bright fragments of the videogames I played as an eleven or twelve-year-old.

Mostly, though, my memories are fuzzy. Blocky landscapes crumble further into abstraction, half-remembered characters jostle for attention, labyrinths hopelessly entangle. It’s hard to know which details are from memory and which are imagination amplified by nostalgia. It feels like centuries since those universes meant much to me. It’s from this distance that I want to write about videogames, especially the places inside them that captivated me as a kid, the dead-ends, empty rooms, and liminal zones where I happily lost so many afternoons.

“A detail from Index of First Lines (32 Months)”

Plopped into a platform-strewn obstacle course, haunted forest, or asteroid field, I would ransack every nook and cranny as if looting a couch for lost coins. I was a relentless adventurer, and one of the thrills of the 8-bit games I grew up with was that it was possible to exhaustively plunder those worlds. Even years before the internet wound its way to my small town, I could be reasonably certain that I had picked every pocket of the little planets that fit inside those plastic cartridges. There were fictional cities I knew more intimately than my own neighbourhood.

I’d draw maps of the worlds I conquered, cluttering graph paper with latticed tunnels and annotations. Invariably, the sprawling cartography of the overworld would give way to the intricate hives of hidden dungeons, maps folded within maps. Excavating one underground lair as meticulously as an archaeologist, I had plotted a tidy grid except for a gap that stuck out like a missing tooth. On a hunch, I bushwhacked back through bats and skeletons to the lone wall that might conceal a secret door, and placed a bomb in anxious anticipation. Its familiar rumble was followed by the glittering trickle of harpsichord that meant the game had relinquished a secret. The difference on the screen was just a few pixels going black, but I felt those bricks fall away, the broken wall as agape as my open mouth.

You’ve actively been working in a slew of different mediums for the several years—poetry, non-fiction, photography, game design, and more. Are there areas in which your visual work and text work intersect? Do you approach different mediums in different ways?

I’m a visual artist and writer, and the two practices often intertwine. I make books and interactive digital works that combine photography and writing, such as Small Landmarks (a handwritten ebook about walking) and Field Notes (a book of photos and poems about writing outdoors). Right now I’m working on a collection of poems about photography and seeing, and on a new book project, Album Rock, about a curious photograph taken on Newfoundland’s Northern Peninsula in 1857.

I’ve been writing code and using computers creatively since my parents first brought home a Tandy 1000 when I was a kid. A few years ago, I made a series of art videogames. I spent quite a bit of time on them (I received an ArtsNL grant to work on Make No Wonder, so I kept track of my time, which by the end was over 500 hours). But I don’t make games anymore. For a while I thought I should write about why I stopped making games, but then I found Darius Kazemi’s Fuck Videogames, which mostly sums it up. Besides being extremely time-consuming, games just didn’t seem to work as art the way I wanted them to. So I wouldn’t call myself a game designer.

In “Comfort Zone,” you talk about challenging the integrity of video games in order to break them down to their component parts, and you do something similar in some of your visual work, especially in a piece like Index of First Lines (32 Months). Another parallel theme in the essay is cartography, which brings to mind the maps at the beginning of Tolkien’s books. What is it about the organization of information that interests you? And did you read a lot of intricate-world fiction when you were younger?

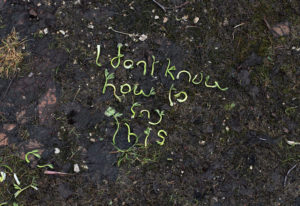

“i don’t know how to say this, from Field Notes”

I’m fascinated by systems, especially graphical or interactive systems, which can be very cold and logical. But I’m also interested in narrative, in the warmth and emotion of telling stories. Both of these things often come together in the Super Nintendo games I grew up with, particularly role-playing games (I loved Secret of Mana, and anything Zelda).

I read a bunch of the Dragonlance books when I was younger. For some reason I never made it more than a few pages into Lord of the Rings, but devoured The Hobbit over and over. Two of my favourite books are still Watership Down and The Phantom Tollbooth, stories where characters make their way through a vast world. Like games, maps can do such a wonderful job of conveying both system and story.

There a thread of nostalgia that runs through right “Comfort Zone.” Have your feelings about video games changed in the time between the era in which it’s set and now?

Well, games themselves have changed immensely since the early 90s. I don’t really play videogames anymore, and when I do, it’s usually replaying something from childhood. Once in a while I come across an indie game that evokes that same sense of exploration and adventure, such as Minecraft or Fez. But mainstream gaming these days seems like a strange and inhospitable world.

With “Comfort Zone,” I wanted to write about that unmappable place between being a kid and being an adult. I also wanted to try writing about videogames differently. So much literature about videogames comes from the game industry, and it can be so commercialized and wrapped up in franchises and fandoms. So I decided to write about my fuzzy memories of places in games, without mentioning individual titles. Thanks for publishing it!

Christopher Evans is the Prose Editor of PRISM international. His fiction, non-fiction, and poetry have appeared in EVENT, Grain, The New Quarterly, Joyland, The Lifted Brow, The Moth, and others.