Former PRISM poetry editor (2014-15) Rob Taylor sat down with Victoria-turned-Vancouver-turned-Toronto poet, and former PRISM poetry editor (2009-2010), Elizabeth Ross, whose debut collection Kingdom was published in Spring 2015 by Palimpsest Press.

A Dying Wasp – Elizabeth Ross

Feels like electricity. I pick up

my bare feet, the wasp arcs – ecstatic

death in the corner of my bedroom,

a crude tattoo of black and yellow

scratched into the hardwood floor –

I’m embarrassed.

Poor wasp, cherry wine and warm grass

are over. How quickly

fall has bruised the maples

on my street, great fists

of hydrangea punched-out blue

swing eye level in the wind.

Is it true you have to sting before you die?

Elizabeth Ross, Crasher Squirrel

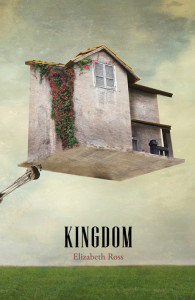

Let’s start at the beginning: Kingdom has a heck of a cover (and back cover). Could you speak a bit about its origins, and what it represents for you in relation to the content of the book?

I’m so lucky: I love the cover. Dawn Kresan, who was also my editor, designed the book – she knew the content well and came up with the striking design. (Talk about wearing many hats and small presses.)

I’m so lucky: I love the cover. Dawn Kresan, who was also my editor, designed the book – she knew the content well and came up with the striking design. (Talk about wearing many hats and small presses.)

What I like most about the cover is the number of ways it can be read. While the ideas of home and homing are central in the book, the image isn’t trying to didactically nail those ideas down – the house is floating. But it’s not clear if the tether – the cable that wraps the spine and is secured to a pastoral tree – is going to tear the tree out, or if the tree is strong enough to hold the house. This ambivalence is my favorite part, and is continued in the house itself, which is simultaneously cute (you could even say it has “curb appeal,” if you were obsessed with real estate like I am) and decrepit, fantastic and menacing. You can almost see the witch’s feet sticking out of the foundation, like in the Wizard of Oz.

I wish I could speak to the cover’s origin, beyond Getty Images. If anyone recognizes it, I’d love to know the artist’s name.

Ok, internet, get researching!

Sticking with the covers, the back page copy for Kingdom refers to the book’s poems as “confessional,” and with titles like “Dear Diary: May 5, 1995” you don’t seem to shy away from the label. The book is set up largely chronologically, with the first section (“Out of Body”) dealing with your childhood, and the book moving forward from there. Do you consider these “confessional” poems? “Autobiographical” poems? What to you think of those labels, in general?

Yeah, I’m not shy of the label. These poems are confessional, autobiographical, whatever you want to call them – I don’t think it matters. As an English student, I became preoccupied with labels, those poetry-101 categories, and while they’re useful in some circumstances, I gave them too much attention and power. Overall, the confessional poets were formative for me – confessional writing is where I come from, or it’s a place that charges my initial work.

Outside the literary stuff, the idea of confession, particularly as an aesthetic, was complicated for me because coming from an Anglican background, repentance seemed to hover in the poems’ equations. I guess repentance is an aesthetic, too. I think I like the idea of writing as repentance, not in the way of asking an external, oppressive force for forgiveness, but in a declarative way, as a statement of values and questions.

The thing I don’t like about confessional writing is that it tends to lead readers to focus on the speaker’s life, rather than the writer’s work. It’s so important to acknowledge the artifice and craft in poetry, confessional and otherwise. A fellow artist was surprised once when I mentioned my editor. I mean, the book started as my thesis, for heavensake; I don’t have an MFA in Feelings.

Years ago, I saw Sharon Olds read from One Secret Thing at the VIWF, and during the Q and A session (I don’t remember the exact question, but it had to do with using one’s personal life for writing material), she said (and I took notes, because I’m that nerdy), “Art bears our life and our memory, and we share the weight.” That’s what matters.

Connected to the above, I was curious, in reading Kingdom, about the sequence in which you composed the poems. Did you write about particular parts of your life at particular moments in your writing life (i.e. Poems about your youth early on, poems about your childhood later, etc.)? Did you find, in assembling the collection, that certain parts of your life were “underwritten” by comparison to others? If so, did it inspire you to write any poems to fill the gaps?

I like the word “underwritten” in this question. It initially made me think of insurance policies, and then of the first unpublished book I wrote that kind of serves as an underwriter for Kingdom, as risk analysis. That manuscript was organized into a deliberate chronology, and while the book didn’t work out, writing it helped me write Kingdom. “Underwriting” also makes me think about how various parts of life – like you say, early childhood – operate much beyond their delineated times.

Funnily enough, the autobiographical chronology you refer to didn’t become apparent to me until another writer pointed it out as an organizational option, and even though it was a great suggestion I followed through on, my first priority was to divide the book into thematic sections, so the narrative is secondary. I did, however, become aware of some gaps that I tried to fill by reorganizing poems within each section. But my main idea was to write poems about personas – areas and ideas – instead of times. I suppose these are blurry distinctions, though.

Do you find you need distance from an event in order to be able to write about it? Are there particular poems in Kingdom that took you longer than others to be able to approach?

I tend to write about things as they happen, but that doesn’t mean the poems are close to being done, or even close to being poems – some take ages, and still aren’t finished, and others go relatively quickly. I wrote “Mastiff” in two intense (I’ll admit, teary) days. That’s pretty rare, though. Other poems, like “Projector” and “Kingdom” had been going through various iterations for years.

I’ve learned that time is a good thing when writing. Since having kids, I have less of it, so I’m much more deadline driven. I have a tendency to push on my poems in their earlier stages, and to work them harder than I did when I was writing Kingdom. But for the most part, I still try to give them some space.

I’m reminded of Jefferey Donaldson and his introduction to Echo Soundings, where he compares poets to sailors listening out a line:

“Poets and sailors have this in common: they sound the fluid element on which they float. They let out a line, so to speak, line that sinks beneath visible surface, more and more line as they go, sounding for the bottom, for the creatures that move along the bottom… It is by the line in their hands and how they feel for it that they know things.”

I love this metaphor. It’s the most concrete way to describe writing I’ve ever encountered. And certainly time and patience, or however you do your sounding – are required.

This book roams throughout British Columbia – Victoria, Nanaimo, the Gulf Islands, Vancouver, the Okanagan, etc. – the places where you grew up, lived and went to school. You’ve lived in Toronto for a little while now – how has living in Toronto changed how you’ve thought of BC?

I’m much more aware of awkward intersections now. I find Gordon Head, the suburb where I grew up, pretty strange. During my last visit to Victoria, I’d go for walks under giant cedars and arbutus, and not see a soul for blocks and blocks except for groups of deer I could have reached out and touched. How creepy is that? And while I was there, a cougar out in broad daylight killed a deer on someone’s lawn. Cougars and deer were always around when I was growing up – I wrote a poem about suburban deer in Kingdom – but not to this extent. The deer “problem,” as many people identify it, has developed to an almost satirical level.

But setting aside zombie deer, in Toronto we’re not threatened by an earthquake followed by tsunami followed by an apocalypse. Although speaking of Oz, there was a tornado warning in Toronto last summer, which was exciting.

Golly gee! I can sense the poems percolating already. But, c’mon, a tornado? Face it, Toronto, you’ve got nothing on us.

In all seriousness the next book going to be all Toronto poems? Would you mind if I recommend against it?

The next book certainly contains snippets of Toronto, but it’s mostly about motherhood, so much worse than a book of Toronto poems.

Poems on Toronto and Motherhood may be equally unbearable, but the poems in Kingdom are far from it. Why not pick up a copy? You can do so at your local bookstore, or from the comfort of your home via the Palimpsest Press website. Or, if you want to be like all the other zombie deer, from Amazon.

You can read more of Rob Taylor’s interviews here.