Interview by A. Niamh Higgins

Laura Farina always seems to be in the right place at the right time.

The Ottawa-born poet, now based in Vancouver, published her first collection, This Woman Alphabetical (49th Shelf, 2005), at age twenty-four—the kind of early success that’s practically unheard of in the literary community.

“It was a very weird fluke that happened,” she admits, “and it was terrifying. But having a first book gets you past a wall—people start to take you more seriously when you say you write poetry and not think you’re a quack.”

As for the experience of publishing as a woman, Farina says, “I think the self-promotion necessary to be a widely-read poet is not exclusive to men, but it is more part of the common male toolbox. I think the numbers of publishers in this country who are men is worth talking about. I think the way we shuffle women’s writing about women’s experiences off into this chick lit void is worth talking about.”

Despite her early success, Farina spent her twenties, like many of us, floundering around—dating the wrong people, making ill-advised moves (“I moved to South Bend, Indiana, because of a boy,” she says), trying to pay the rent. Searching for home.

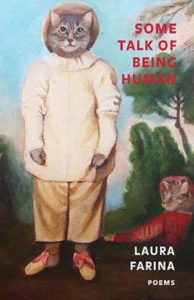

Her most recent book, Some Talk of Being Human (Mansfield Press, 2014), is in many ways a chronicle of this search—a slim volume of strange, spare, exquisite poems, written over nine years in Ontario, Banff, Vancouver, and the States.

“I was moving constantly,” Farina says, “and I was thinking a lot about home—can you take it with you when you go, and once you’ve lived somewhere, are you always going to miss it? Home is like a battery charger, and if you don’t have it, you feel cast adrift. And I did, for a long time. Like, is it here? Can I live here?”

And like so many young creatives, Farina has had her share of uninspiring jobs. A poem titled “Customer Satisfaction Survey” reads, “From behind shatterproof glass / he can finally say / what he thinks of me. / It is not all positive.”

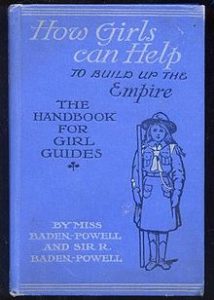

She had a stint working for Girl Guides of Canada, during which time she became obsessed with the first ever Girl Guide handbook, How Girls Can Help to Build the Empire. Farina and her colleagues spent their lunch breaks in the graveyard across the street performing exercises from the handbook—tying knots, practicing first aid, tracking animal prints.

She had a stint working for Girl Guides of Canada, during which time she became obsessed with the first ever Girl Guide handbook, How Girls Can Help to Build the Empire. Farina and her colleagues spent their lunch breaks in the graveyard across the street performing exercises from the handbook—tying knots, practicing first aid, tracking animal prints.

“My intern designed underwear with the first sentence of the handbook on the ass,” she says. “It was, ‘Decadence is threatening the nation.’”

These days, she teaches writing at Christianne’s Lyceum, a local organization that offers arts- and literature-based programming for young people. The Lyceum is a tiny, magical place where children drink tea in the fairy garden, weave bracelets inspired by poems, and adjourn to a nearby park for games of quidditch.

“Kids say amazingly poetic things quite frequently,” Farina says. “Like, this kid was scribbling intricately and she looked up at me and said, ‘this is the path the wolf took through the woods.’ That’s an amazing line, and that happens a lot.”

There’s a warmth and humour to Farina that belies the melancholia of some of her poems: “(t)he difference between me / and water,” she has written, for example, “is that no tall man / ever longed for me on a hot day.”

A few images recur and recur in Farina’s work: “I’m obsessed with windows and the wind,” she says. “Windows can be open, wind can rush through them, but they’re going to stay put. They’re a barrier between your home and the outside world.” Many of her images have a charming mundanity to them; she writes about eating processed cheese in her parents’ basement, losing her sunglasses in Florida, walking by the ocean after brunch.

“Sometimes when we hear the word accessible applied to poetry, it’s like when a girl in grade 8 says she likes your shirt—it sounds like a compliment but it’s not a compliment,” Farina comments. But her poems are accessible in the best possible way—they invite you to come inside, but throw you off guard when you get there; the images seem simple, but they ring in your ears like an echo, long after you’ve put down the book.

“Sometimes when we hear the word accessible applied to poetry, it’s like when a girl in grade 8 says she likes your shirt—it sounds like a compliment but it’s not a compliment,” Farina comments. But her poems are accessible in the best possible way—they invite you to come inside, but throw you off guard when you get there; the images seem simple, but they ring in your ears like an echo, long after you’ve put down the book.

“No matter how lonely or weird you feel about the world,” Farina tells me, “there’s this part of you that’s like, people love you and there’s pizza and there are good things in the world. I think I write with that part of myself turned off, and it makes the images in my poems stronger and weirder. No one’s posting pictures on Instagram of the mess of their lives, whereas I think people are more okay writing about the mess of their lives.”

After all of her searching (and despite an occasional pang to settle down in Wolfville, Nova Scotia) Farina has found her home here in Vancouver, or “No Fun City,” as it’s often called, a place with a reputation for being unfriendly. But this couldn’t be farther from Laura’s experience.

“I find it so welcoming. Because it’s so walkable you end up running into people a lot and feeling like part of a community. And it’s a city where things happen, which matters to me, as it turns out. Like, I don’t want to live in a city with no drag queens. And I never go to drag shows, but the idea that I could is amazing to me.”

And she’s found her person, too—Farina’s husband, Dan Bates, is a local actor / puppeteer.

“Hanging out with someone who wants to make out with you is often more fun than writing poetry,” she admits, “or at least it seems more fun at the moment when you have to choose. But my husband is really awesome at making space for me to write poems and amazingly doesn’t seem to have any aversion to having his most personal moments in print.”

Farina creates poetry and community everywhere. She formed a writing group, for example, by connecting with a woman her friend met at the bus stop. And last summer, she and another friend handed out lemonade at Kits Beach with poetic observations written on the cups. They’re on a quest to scatter poetry through Vancouver, and they have so many ideas: stickers plastered around the city that say, “Margaret Atwood is watching you”; “exquisite corpse,” a surrealist game that creates poetry through chance; a poetic bonfire.

Farina looks like a lucky person—to have published so young, to have developed a career as a writer, to have found, at last, her home. But the more time I spend with her, the more I suspect that luck might not have much to do with it at all. Farina is more than hard working, more than smart, more than talented—she has a gift for creating, wherever she goes, something beautiful.

A. Niamh Higgins lives in Vancouver.