By Robert Colman

Books discussed:

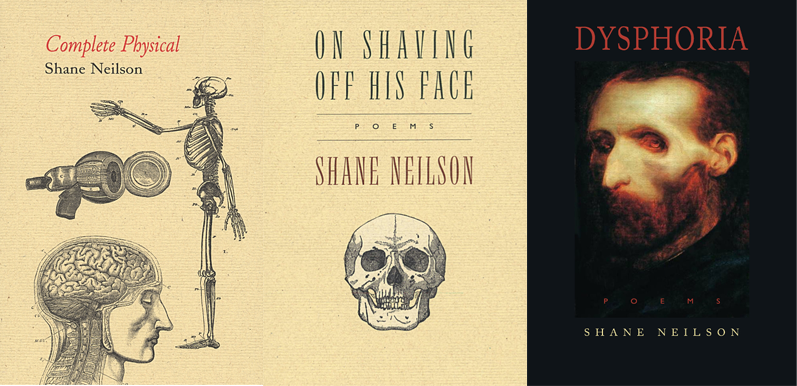

Complete Physical by Shane Neilson (The Porcupine’s Quill, 2010)

On Shaving Off His Face by Shane Neilson (The Porcupine’s Quill, 2015)

Dysphoria by Shane Neilson (The Porcupine’s Quill, 2017)

According to Deadly Force, a CBC News investigation into fatalities involving police in Canada, more than 460 people have died in encounters with the police across Canada since 2000. A substantial majority of these people suffered from mental health issues or substance abuse. If you missed the CBC investigation in early April, when it first came out, I wouldn’t be surprised. It was reported and then lost, for most of us, in the swirl of 24-hour news coverage.

A further breakdown shows forty-two percent of those who died in encounters with the police were, according to the article, “mentally distressed.” This is disturbing, yet it is still seemingly easy for many to set aside. Few of us openly condone the idea of police violence, but confronted with these facts, are we willing to bear witness? What does it mean to accept and support those who live with mental illness every day?

Poet, editor, and physician Shane Neilson’s poetic trilogy on affect—the books Complete Physical, On Shaving Off His Face, and Dysphoria—give both a first-hand account and a medical primer on what it’s like to live with and treat illness. They can be seen as a guide to understanding mental illness in particular and accepting that society can do more to connect with people who live with mental illness in meaningful ways — those living with mental illness need good medical aid, but they also need connection and compassion.

Complete Physical

Complete Physical is a book about failure—the failure of medicine to cure and the limits of the doctor in his white coat. Take the poem “Campanology”, for instance, in which the doctor tries to find words of comfort, “but all that comes out / is a sound like a tolling bell.” (19)

This book chronicles the doctor’s meetings with patients before and after diagnosis and shows the physician wondering at the role he plays. There is love there, in the struggle to connect. Because death is always so close, people need to be heard now:

I parcel out parts of me, fifteen minutes apiece.

I want to ask: were you told you were loved,

are the bills past due and all you can do is fight

with Mike about what was spent on nothing?

Love again. Damn. it’s more important than

your sore throat, than your cough… (50)

Complete Physical also finds Neilson at play with form, demonstrating his command of the villanelle, the sonnet, the sestina, as well as freer lyric poems. In all cases, it is the poet pondering the role of a doctor trying to understand how to live well amongst the inevitability of life’s losses. The form poems serve to suggest the doctor is feeling in control. For instance, the first sonnet in the book, “Standard Advice,” reads, “if you are sick, I will marshal what I have.” A later sonnet, “Taking Charts Home After Work,” suggests through its form that the doctor tries to master a sense of control, even though he is staring at his limitations: “Kerchink / goes the mechanism of my own care, too brief, / and I wonder what the chief lesson is, and who is chief.”

On Shaving Off His Face

While an accomplished collection, Complete Physical is also lyrically straightforward and takes few chances. Thematically and poetically, On Shaving Off His Face is a leap forward and a greater challenge for the reader. Thematically, it tackles mental illness directly. This is a subject that is important to Neilson as a physician, but also as someone living with bipolar disorder.

Poetically, Neilson’s lyrical shift is announced in the first poem, “General Preamble,” which introduces a full section about the face as a vehicle for the expression of illness:

They looked and knew what was wrong. Your face designed to break and

break again on illness. Blood and alcohol the isolate you wear as

helmet. But skin-masks envelop grief-masks. More blood, alcohol, and

always need. (13)

On Shaving Off His Face is divided into three sections that serve as ruminations on slightly different but related topics. The first is a series of eighteen poems about illness as expressed by the face. The emotional urgency of that first poem is followed throughout the section.

The second section, however, is where Neilson takes unusual leaps with form and content to further explore illness. It is devised as an imaginary academic conference in which a variety of people discuss how facial expressions signal emotion. This includes physicians such as Benjamin Rush, but also people who are not medical professionals, such as Fleet Foxes singer Robin Pecknold, who is transplanted to a Pennsylvania hospital in 1786 in the poem, as well as Lead Belly, Al Capone, and Ashley Smith. By setting up multiple narrators, the poet is free to expand his subject beyond what might be seen as strictly his personal experience. And Neilson takes chances. He has Rush sing his own version of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and he has Ashley Smith present her own case history. “An Able Physiologist 9” is a good example of Neilson pushing against the boundary of the lyric to relay the distress of confinement and incarceration:

Just three years ago, the

Petitcodiac wondered if it could arise and go now. I walked to the river

and threw dreams into its polluted breast. Moncton’s grime and debris

coated the green but yet kept it afloat, armouring it. (67)

The third section of On Shaving Off His Face is focused on the struggle of the author/narrator to cope with his child’s illness. This partial stanza from “Fast” echoes, in the phrasing of its first four lines, both the singsong rhythm of trying to soothe a child and the painful experience of being unable to do anything:

On the road out of Guelph. Black. In the back,

he’s belted in the car seat, choked, rigid, then slack.

You sit with him, sing ‘Wheels on the bus’.

The snow comes down. What is it with us?

That pain unites? Rearview mirror:

lights and faces, in love. I want to stop the car,

walk off into the forest, and come out starving, pure,

with a cure. But the thought doesn’t last. I drive

knowing that I took my chance. I have nothing else.

And so we go to another hopeless wilderness. (94)

The above is a good example of Neilson’s facility with rhyme. The first four lines play with the “Wheels on the Bus” rhythm, but he doesn’t feel beholden to staying the course. The next lines fissure with slant, internal rhyme, and the declarative (“the thought doesn’t last”). In the last two lines, “else” and “wilderness” cling to their final consonant to bond, but like the narrator it is weakened compared to that bold, rushing (but beaten in a different register) parent in those top four lines. The poem also hearkens back to Complete Physical in this association of pain with greater connection.

Dysphoria

The eighteen-page title poem in Dysphoria is one that I return to regularly for its dense narrative and its plea for those who are ill. The narrator is a man in a solitary room in a psych ward receiving an injection to treat an acute episode. He welcomes the healing value of the medication, while pondering a lost love (through lines from Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman”), addressing the insistent voice in his head (which repeats “Climb the water tower” throughout), and discussing the pain of seeing others like him killed by police who react to illness with violence:

…I thought it would all

work out, you know? But hard work isn’t strategic. Work

smarter, but don’t fear the first responders? The smartphone

in my tinfoil hat says that I’ve misunderstood. In the stadiums,

I lose the signal of another death by cop….

The entire poem is built from taut couplets that both give space to the narrator’s ideas on the page and construct a narrative that ping-pongs from emotions to ideas.

“Dysphoria” is many things, but among them is the narrator’s wish that he and his ‘people,’ those who are similarly affected by illness, may be allowed to live without fear of harm from others. As the last line says, “If we can’t live in peace, then let’s die in peace.” In other words, don’t let first responders be last responders.

The second section of the book reimagines Benjamin Rush’s early nineteenth-century textbook Medical Inquiries and Observations Upon the Diseases of the Mind. It is Rush’s sympathetic nature that no doubt encouraged Neilson to use him as foil here, with recommendations to interns about how to treat patients, as well as an account of an escaped patient and imagined documentation from other medical professionals. One of the most compelling poems is “i sing the body electrocuted,” dedicated to Robert Dziekański:

He sings the body electrocuted, a song in which death is never safe.

We are the ones to carry the dead, to make myths of the dead, and to

carry their myths.

His message is one we can only hope to not understand, in the least

violent way.

Sing, my ill brothers and sisters, of holding charge in the body! (65)

Here, the narrator emphatically calls for the ill to live as they can, and vibrantly. For those who are not the narrator’s brother or sister in illness, it is one of many places in Dysphoria where one can’t but pause and ponder how we can be better supporters of those who are ill.

Another poem that I return to often in this collection is “Ripley’s Aquarium,” in which a father, in the midst of the pain of his own mental illness, attempts to be present for his son. Perhaps I feel that I’ve been that boy, or that man, and the words resonate:

I wish I were less; and lesser I shall be.

My son and I stand on a conveyance.

The fish neither single file nor school,

but arranged as coral accumulative—

as death dispersed, shard-hardened.

Motion scrapes the transparent glass.

He likes the stingrays. Me, my mind’s not right.

Other families oooh and ahhh—what luck.

My son and I, we’re silent; he sees electric

as I fight the urge, as always, to close my eyes. (80)

This is the plight of those with non-visible dis/abilities in the world. Neilson creates distance and a sense of dissociation with his use of the word “conveyance”—as if he and his son are bottles on a production line. The fish are a motion that “scrapes” the glass. You can almost hear the pain of seeing this when in the midst of pain. And “my mind’s not right,” a direct quote from Robert Lowell’s poem “Skunk Hour,” nods towards another line from the same poem: “I myself am hell.” The struggle to be present for those we care for while trying to manage illness is perfectly captured here.

With this section of Dysphoria, Neilson comes full circle to where he started in Complete Physical — back to the daily struggle we all face in addressing our inevitable losses. Yet, Neilson has managed to give the reader a view into how mental illness can make life that much more difficult along the way.

Neilson’s poetry itself matures from volume to volume. Where Complete Physical is straight lyric poetry that is common in early twenty-first century Canadian literature, On Shaving Off His Face is a jarring, muscular exploration of ideas through play in prose and poetry. Dysphoria finds Neilson mastering the balance between the two. It is a difficult and sometimes uncomfortable read, but it insists on being revisited. The whole trilogy stands as necessary reading at a time when society continues to demonize mental illness rather than support those who live with it daily.

Robert Colman is a Newmarket, Ontario-based writer and editor and the author of two full-length collections of poetry, Little Empires (Quattro Books 2012) and The Delicate Line (Exile Editions 2008), and the chapbook Factory (Frog Hollow Press 2015). His new collection, Democratically Applied Machine, is forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2020.