Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands

Kate Beaton

Drawn and Quarterly, 2022

Review by Ellie Eberlee

The headline published May 1, 2008, by the New York Times, read as follows: “Canadians Investigate Death of Ducks at Oil-Sands Project.” The article was brief but memorable—as Kate Beaton, former oil sands work camp employee, graphic memoirist, and author of Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, pointed out in an interview with podcaster John Moe, it was “the first time the world’s eyes really turned to the oil sands with concern.” Studying Beaton’s illustrated reconstruction of the article in Ducks, one can understand why. The artist bolsters the Times’s text with an image of two lifeless mallards, their bowling pin-shaped bodies sinking beneath the dark, indelible scribbles of a Syncrude-owned tailings pond. For many, ducks remain a striking and accessible emblem of the callous destruction unfolding amid Alberta’s remote tar sands. Stamped beneath the jacket cover of Beaton’s graphic memoir is a single duck in flight, its surface as smooth and iridescent as a gasoline slick.

Yet Beaton’s memoir presents the murder of hundreds of birds as merely one in an awe-inspiringly painful litany of injustices (environmental and otherwise) brought to bear on the inhabitants of northern Alberta. Saddled with student loans following a liberal arts degree at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick, Beaton arrives in Alberta at twenty-one, leaving her closely-knit coastal hometown of Cape Breton as part of a mass exodus of Maritimers hoping to reap the riches purportedly provided by the western province’s ever-expanding oil projects. Months in, Beaton forgoes the more regular rhythms of Fort McMurray, where she waitresses and commutes from an apartment in town to Syncrude’s nearby base mine in Mildred Lake, for the near full-time labour entailed by the work camps—the kinds of places where, for an abundance of hours and with no need to make rent or buy groceries, “the real money lay.”

Beaton is outnumbered fifty to one as a woman at Opti-Nexen’s enormous Long Lake work camp. From her post as a tool crib attendant, she distributes armloads of equipment to various employees every day, many of whom approach the counter solely for the purpose of exchanging a few would-be flirtatious words (as she complains to an apathetic manager, several “ask for gloves they already have”). At off-shift parties, Beaton learns to keep her guard up. An unblinking set of pages depicts the harrowing quietude of the author’s first sexual assault at camp. A colleague offers to escort her back to her room, only to lock the door behind her and insist that she “Come here, now.” The ensuing column of wordless, impenetrably black panels proves some of the book’s hardest to look at.

Still, the oil sands—even the blatantly gendered, gargantuan otherworld of the camps and their unrelenting work schedules—have some redeeming qualities. Beaton’s excitement in paying off her student loans after two years of work is palpable. She allies herself with other misogyny-worn women and the occasional male softie. One example is Norman, the mechanic and self-taught photographer who prints high-quality images. He captures the northern lights and a rare rainbow arching over the Albian mine, so Beaton has a “little piece of [Alberta] to take with [her]” when she leaves. As Beaton writes in the book’s afterword, “there is often a tendency to want to characterize the Northern Alberta oil sands as either entirely good or entirely bad—the jobs and profits vs. the climate rattling destruction. But,” she cautions, “over my time there, I learned you can have both good and bad at the same time in the same place, and the oil sands defy any easy characterization.” It is Beaton’s monochromatic graphic form that allows her to cull both good and bad—to literally sketch the various, subtle shades of grey which coloured her time at camp.

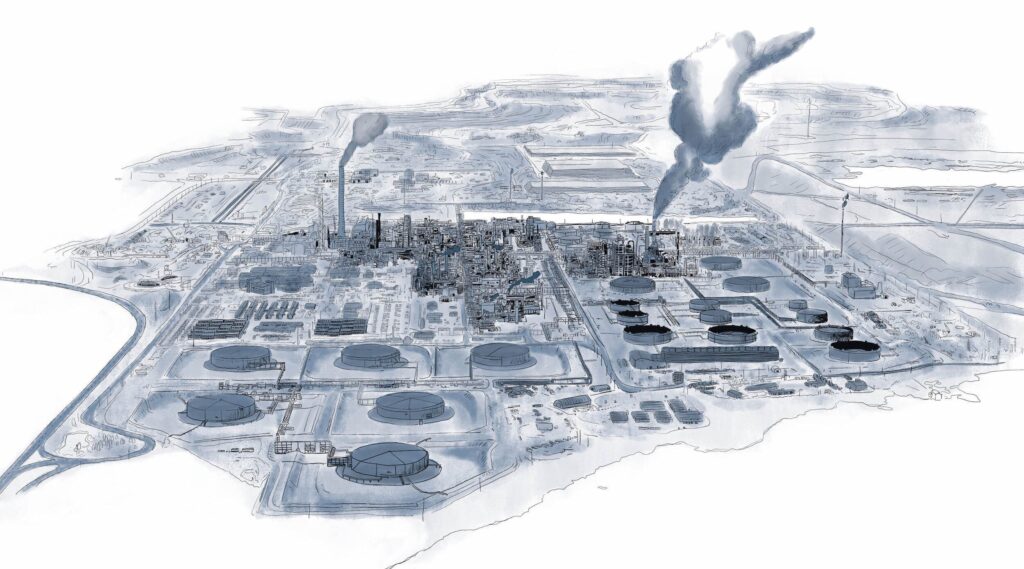

Indeed, turning the exquisitely illustrated pages of Ducks, it is hard to imagine Beaton’s experiences—this place, these people—so vividly expressed by any other medium. A double-page spread depicting Shell’s Albian Sands, its shuddering smokestacks and mammoth-sized machinery towering well beyond the book’s 18.5cm by 23.5cm confines, dramatizes labour on an ineffable scale. Beaton’s inky washes and scrupulously observed line drawings evoke the mines’ aesthetic marriage of immense, industrial ugliness and unexpected beauty. And her exhaustive sketches of the general labour trailers and meager, almost prison-like living conditions at the Long Lake oil sands upgrader project emphasize how, as Beaton writes in her afterword, “camp life fosters a unique set of mental health challenges in an environment that is probably the least suited to contend with them.” They suggest specific ways in which, despite the workers’ best efforts to find a sense of home amid these conditions, “the boredom, isolation, and depression add up for many—and for some, are too much to bear.”

Each time Beaton moves mines she devotes a single page spread to a kind of illustrated dramatis personae. These not only provide a graphic “headshot” of many of her friends and coworkers, but enumerate their names, positions, and hometowns. On one hand, this visual roll call perforates the mass monolith of oil-working employees Beaton encounters over her two-year stretch—for, as she writes, “the humanity of camp workers is often lost in the popular image we have constructed about who goes there and why.” On the other, these portraits begin to leach into one another as the narrative progresses. Over time, it becomes difficult to distinguish between, say, Ambrose, a mechanic foreman from Newfoundland at the Syncrude Aurora mine, and Russell, a warehouse foreman from Newfoundland at Long Lake. The result is a paradoxical sense of humanity and inhumanity, highlighting the workers’ precarious status as, in the words of Beaton’s cab driver upon her arrival in Long Lake, a “shadow population.” This sense of dispossession and identity loss has devastating repercussions. More than once, Beaton learns that long-time coworkers have silently suffered from alcoholism and addictions to cocaine and Percocet. Some die of overdoses. Others, like Ryan, the warehouse foreman from British Columbia, leave and do not return.

Beaton’s economic dialogue operates as a similarly complex tool. Her speech balloons provide ample opportunities for wry, conversational humor. Beaton’s cousin, who she reconnects with at Long Lake, calls the job “grunt work with a bunch of dropouts and endless country music playing.” The crew laughs at a handful of British recruits who keep asking for “spanners instead of wrenches and wellies instead of boots.” Her speech balloons also provide a forum for deeper, difficult exchanges—stilted, half-realized musings perhaps better suited to the immediacy of dialogue balloons than more polished, conventionally formatted prose. In a patchy, suddenly poignant discussion over coffees at a local Tim Hortons, for instance, Beaton and her sister Becky (who has, by then, also migrated to the oil patch,) wonder how the men they knew back in Cape Breton would fare amid the camps’ cold-blooded, patriarchal environments.

The form of the graphic memoir thereby enables Beaton to undertake a visceral, thorough likeness of an often inhuman world (or what she calls, “a uniquely capsuled off society,”) while retaining sympathy for the profoundly human injustices at its core. More broadly, the former oil sands employee’s masterwork illuminates the storytelling possibilities of graphic memoirs for representationally challenging subject matters like sexual assault and substance abuse. Where more orthodox or prevailing prose formats do not suffice, graphic forms like Ducks extend additional written and visual vocabularies for crafting compelling narratives about the kinds of individuals, environments, and events which—unlike Beaton’s titular drowned ducks—do not typically make the headlines.

Ellie Eberlee holds her Master’s in English Literature from the University of Oxford and is currently undertaking her Publishing and Editorial Certification at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. A native of Toronto, she has worked for Oxford University Press and interned with Harper’s Magazine and the New England Review. Her essays and reviews have appeared or are forthcoming in Guernica, the Literary Review of Canada, and The Chicago Review of Books, among other venues.