In this Double Feature, PRISM international is proud to share Deborah Vail’s review of Kathryn Mockler’s book Anecdote, followed by Vail’s interview with the author.

Anecdotes

Kathryn Mockler

Book*hug Press, 2023

Diving into Anecdotes, Kathryn Mockler’s unique debut collection of short fiction, personal stories, and critical observations, is like inviting an old acquaintance over for tea, and she arrives with Tequila; you’re not sure where the conversation is headed because her delivery is as unconventional as the words she speaks.

Organized in four distinct sections, the author filters complex issues like sexual violence, schoolyard bullies, unhappy adults and climate crisis through her own personal experiences. The collection opens with a short story, “The Boy is Dead,” where readers learn the circumstances of an unloved boy’s life. It’s harsh, sad, and numbing because the subject matter is all too common. Mockler speaks directly to her audience and pulls us into the heart of the story when she says, “You might be disappointed to know that the boy was not in fact murdered.” Apathy and neglect killed him, she tells us. She pulls us even closer with her final sentence,“I wrote this story about a boy in the hope that you would find it more interesting than if it had been written about a girl with the same experiences.” Suddenly, readers are forced to ponder another strong theme embodied in this collection – misogyny.

Using short fiction and anecdotes taken from elementary school through her first year of university, Mockler recounts numerous traumatic experiences; negligent parents, mean girls, religious predators, and sexually aggressive men. Together they offer us a slice of the author’s life without relying on her hard-earned wisdom to make sense of it. That challenge she leaves to her readers.

Not all of her anecdotes resonated with me, although each one contributes to an overall picture of how a person can be shaped by their recurring experiences. In “The Pad” Mockler writes, “Not only was I an ugly duckling, but I was also weird and gross. And once someone decides you are weird and gross . . . there’s no going back.” Truth for anyone who spent their school years trying to shed a cruel nickname.

One anecdote however, felt eerily familiar. “The Fuck Truck” depicts a Friday night where Mockler and another young female friend hit the bars on Montreal’s Crescent Street and soon find themselves in the back of a van with three young men who are suddenly not as nice as they were in the bar. Terrifying and all too real, this story brought me back to my first year at Concordia University and my Saturday nights spent prowling the bars on this same street. The dance between prey and predator unfolds, and the stakes are always so much higher for young women. Mockler depicts this in the ending of “The Fuck Truck,” where she and her friend have no choice but to throw themselves out of a moving van, “I squeezed my hands together and told myself that if I got out of here alive, I would never do this again—as if someone trying to scare or humiliate or kill me was somehow my fault.”

The third section, This Isn’t a Conversation, was, for me, the most challenging to absorb. Black pages with white print that suggest a graphic novel without illustrations were snippets of overheard conversations, diary entries and found texts. They merged to create a common theme of anxiety over the environment, politics, and being alive, making the sections I had already devoured feel even more profound.

The collection ends with the section, My Dream House, which depicts a stand-off between The Past and The Future. Their relationships are void of compromise, often hilarious as they bicker like a couple who have been married for far too long and waffle between fantastical and meditative. It’s no surprise when The Present arrives and tries to mediate. But it’s too late. “The Past . . . was fast asleep.”

This unique collection, told with a poet’s intuitive ability to hone in on truth, will make you stop, hold the book against your body and wish more than anything that humans were kinder to each other and planet earth. Some readers may put this book down and say its content and design are too unconventional and too blunt. To use Mockler’s own words, “I hope environmental catastrophe doesn’t interfere with your self-actualization.” I didn’t interpret this line as sarcasm but rather the brutal facts about existence in this era.

From kids bullied in a schoolyard to environmental collapse, Mockler sucker-punches her readers with the courage to shine light and comment on serious issues. Her writing is uncommonly direct and she does not try to sugar coat the hopelessness that many of us experience when contemplating the issues she puts forth. Yet, she does give us the only thing that could possibly manage such harsh reality— outrageously good humour.

Getting to know Kathryn Mockler: An Interview by Deborah Vail

Deborah Vail: Hi Kathryn, thanks for agreeing to do this interview for PRISM international and congratulations on the success of your collection, Anecdotes, which coaxes your readers to think deeply on issues that haunt many of us.

How does it feel to garner so much attention for this project and how do you imagine this success will influence your future creative endeavours?

Kathryn Mockler: I’m very grateful to be shortlisted for the Danuta Gleed Award and the Trillium Book Awards. The authors on these finalist lists are exciting, and I’m happy to be among these wonderful writers.

My book is kind of weird, so I was quite shocked.

Anecdotes deal with issues that are important to me such as misogyny, violence, the climate crisis, and oppression. If getting on an award list helps interest readers then that’s a good thing. I’m happy that it also benefits my publisher, Book*hug, who took a chance on this unusual book.As for my future creative endeavours, I haven’t really thought that far ahead. Awards are not something I consider when I’m writing.

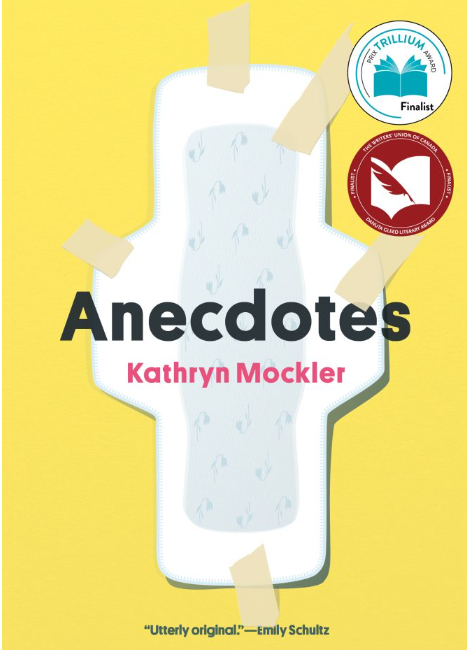

DV: The cover of this collection, a maxi pad, is eye-catching. It’s what made this reader reach for it. Can you tell me how this image was chosen as the cover photo and about the title.

KM: All credit for this cover goes to writer, editor, and designer Malcolm Sutton who both edited and designed Anecdotes. I’m eternally grateful to Malcolm for this wonderful cover, which I think captures the tone and humour of the book exquisitely.

The cover is based on one of the autofictional pieces called “The Pad” where the pre-teen protagonist sticks a maxi pad on her wall and gets shamed for it by someone she admires. Malcolm put this design together and sent it to me. I loved it so much I burst into tears. It never would have occurred to me to put such an image on a book, which indicates how deep period shame runs. But when I saw it I knew it was perfect!

DV: To what extent do you consider your readers’ perspective as you write?

KM: When I’m writing first drafts, I’m thinking only about what stories I need to tell. Writing for me is often impulsive and compulsive.

My consideration of the reader begins when I’m editing. I have a screenwriting background, so I think about what context the readers need to understand the characters and the situation. I think about how the readers will move through the story structurally and what might be necessary for them to connect with what I’m trying to say.

DV: Your anecdotes are raw and often disturbing. It feels like you don’t hold back anything. As a writer just beginning to tackle memoirs, I find myself holding back from the raw truth of my experiences. What advice can you give reluctant truth tellers like me?

KM: I find the genre autofiction is a good one for me because it allows me to both speak frankly about some personal experiences while also having the freedom to fictionalize what I need to. The label helps me creatively even though it is often dismissed.

As for advice, I would just try to write without thinking about who might read it. Write about an event exactly as it happened like you are reporting on your own life. You can always cut and change the details later, but it’s important to get your story on the page before you begin to censor yourself.

DV: Your work is packed with humour as well as personal reflections on difficult aspects of your childhood. How do you see past traumas as shaping your creative mind?

KM: Humour is just how I cope with living in this chaotic terrifying nightmare of a world.

DV: How do you handle criticism?

KM: Very well actually. I’m much better at handling criticism than compliments. My film background has helped me develop a thick skin around criticism and feedback during the editing process.

On some book review sites I’ve had some funny negative reviews. One reader was mad about the length of the stories, and another was annoyed that it wasn’t a novel, which is funny because it’s not a novel. My favourite critique was a reader who called the book “fake deep” and I’m taking that as a compliment. Inspiring irritation or rage is kind of satisfying. I once wrote the most hated haiku in Canada, so I take it all with good humour.

Criticism only really hurts me when there’s some truth in it, and if I feel that kind of pain then I ask myself why and try to face whatever is causing the upset.

DV: Who do you read, and what is it about their work that intrigues you?

KM: I read all genres, but I’m mostly interested in writing that has a critical or political lens.

Here are some recent books I’ve read that I recommend:

I love Saeed Teebi’s acclaimed story collection Her First Palestinian. In April I published an excerpt in my newsletter from the story “Enjoy Your Life, Capo” which is set in Toronto during the early pandemic years and follows a Palestinian software engineer who develops a breathing app he hopes will help his chronically ill daughter. However, the only buyer makes him complicit in the surveillance of his own people.

Shashi Bhat’s Death by a Thousand Cuts is a funny, smart, and beautifully written collection of stories—some of which fall into the domestic horror category. In addition to tales of bad dates and shitty boyfriends, these stories also deal with fraught family relationships, illness, ostracization, disconnection, and disfigurement.

I recently re-read Jacob Wren’s Rich and Poor (2016) about a former classical pianist who plots to kill a billionaire, a satisfying read in this time of excessive corporate greed.

I’m currently reading The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex (2017) by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence which takes a critical look at the ways in which non-profits can neutralize social dissent.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Raised in Montreal, Deborah Vail now lives on a secluded acre in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia. Her book reviews, interviews, short fiction, and creative non-fiction have appeared in several Canadian journals including Grain, The Antigonish Review, and The New Quarterly to name a few. In 2020 she completed an MFA in Creative Writing from UBC.