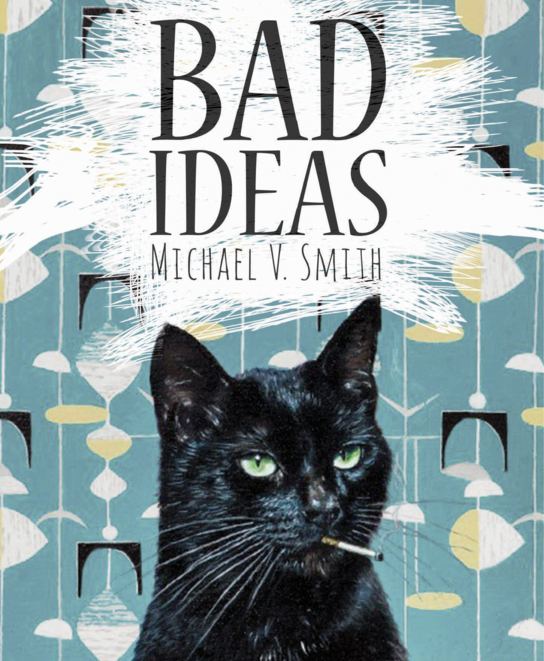

Bad Ideas

Michael V. Smith

Nightwood Editions, 2017

Interview by Matthew Walsh

Bad Ideas, Michael V. Smith’s newest collection of poetry was just released with Nightwood Editions this year. Described on the first inner page as a “book of anxieties,” the book is full of little things: prayers and dreams that examine identity, queerness, and politics. It was great to catch up with the Lambda Literary Award finalist about his new work, and all his bad ideas.

I was curious if you did any sort of dream journaling while you were working on this project. What is one dream that didn’t make it into the book?

These dreams are actually from other people. None of them are my own. About ten years ago I asked a bunch of friends and family to keep a record of their dreams for two weeks. I saved them all in one file, without attaching names to them, and then put them in a drawer for the decade. Most of them are verbatim, with some minor edits—like trimming back—but a few dream poems I pushed a little further, inserting some images or massaging an idea I thought I saw.

Sometimes when I am writing I stumble across a memory, a moment I had supressed or forgotten until it is triggered for whatever reason. Like a summer I spent learning to row boat. Did anything like that happen to you?

Some of these poems jumped for me in surprising ways, like ‘Prayer for Humility’, where my father’s catheter appears, and an ekphrastic poem about a John Kissick painting that somehow dredged up a memory about my parents fighting when I was young. That memory was totally unrelated to the painting, obviously, but the emotional moment of the painting found an echo in a memory. I love how the poem—and the experience of writing it obviously—work at finding the bridge between those two events. Two moments calling to each other, or maybe the present moment calling and the past answering back.

The book was composed partially with dreams your friends and family had. Was there something new you learned about the people, or something that surprised you about their dreams in particular?

I can’t say I was surprised by the content of the dreams as they related to a particular person—like, everyone’s subconscious is a surprise, I think. But I was surprised by the details of their dreams, surprised by how clearly some logic seems to be at work. It may be hard to say what dream logic is, to put our finger quite on it, but you still recognize it, you know? We recognize its associations. We’re intimate with a dream’s tangential slides sideways. I love how the dreams, and these poems, sort of give us an answer to a question, but both are fuzzy. There is such clarity and such… crypticism, if I can make up that word.

Everyone has had some bad ideas in their lives, whether acted upon or not. Could you share one of yours?

Oh, I wrote a memoir cataloguing so many of my personally bad ideas. I’ll just say, “Reference My Body Is Yours.”

What was one of the hardest obstacles in putting this collection together, and how did you overcome it?

For a long time I felt like the poems just hadn’t quite found themselves, like the form wasn’t really working yet. They were too flat on the page. They sounded so much better than they looked. And over the last year of putting the book together, I read a bunch of great new writers—Raoul Fernandes, Kayla Czaga, and Ben Ladouceur—which helped a lot. Many of the new poems came from reading their books. Then I read three poems from Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds and it felt like a crevasse opened up in my brain. Full of ideas. I edited the whole book that day, moving things around, changing the shape of poems. When I was done, it felt like the poems had been teenagers, and suddenly they’d grown up and moved out on their own. Everything fell into place. That’s partly time, much to do with reading, and definitely only possible by asking questions.

I loved the line in the poem “Prayer for Promiscuity” that reads “the night teaches us/what we never had”. There are so many good lines in the book, and poems, but this one stood out. What inspired it?

The poem itself is me trying to reconcile my years of fairly compulsively cruising for sex. To capture that moment. In some ways, a poem is like an idea under glass, you capture it, catalogue it, and can turn it over in the hand to see its parts. So I wanted to get at the thingness of cruising. And so I sat inside my memory of the sensations of being in the park at night—not really the sex stuff, but more to do with the atmosphere, the sense of magic that comes at night in the park. Being in the dark with other men you can only make out in the distance as darker forms. And all that longing the obscurity helps to make. Anonymity as an imaginative gift, you know? Like, you may not know who this person is, but your imagination is happy to invent it. The dark unlocks your fantasy. That right there can be so addicting.

Matthew Walsh is a poet and short story writer whose work has appeared in Joyland, The Malahat Review, Arc, Bad Nudes and others. twitter: @croonjuice