Review by Annick MacAskill

Last October, my friend David Alexander (Modern Warfare, Anstruther Press, 2016) and I went to an Anstruther Press and Baseline Press chapbook launch to see a few poets we knew. When I heard Aidan Chafe read from his debut chapbook, Sharpest Tooth (Anstruther Press, 2016), I immediately wanted to buy his collection. I was drawn by Chafe’s strong imagery and measured, almost laconic consideration of the destructive ferocity and violence of the natural and human worlds.

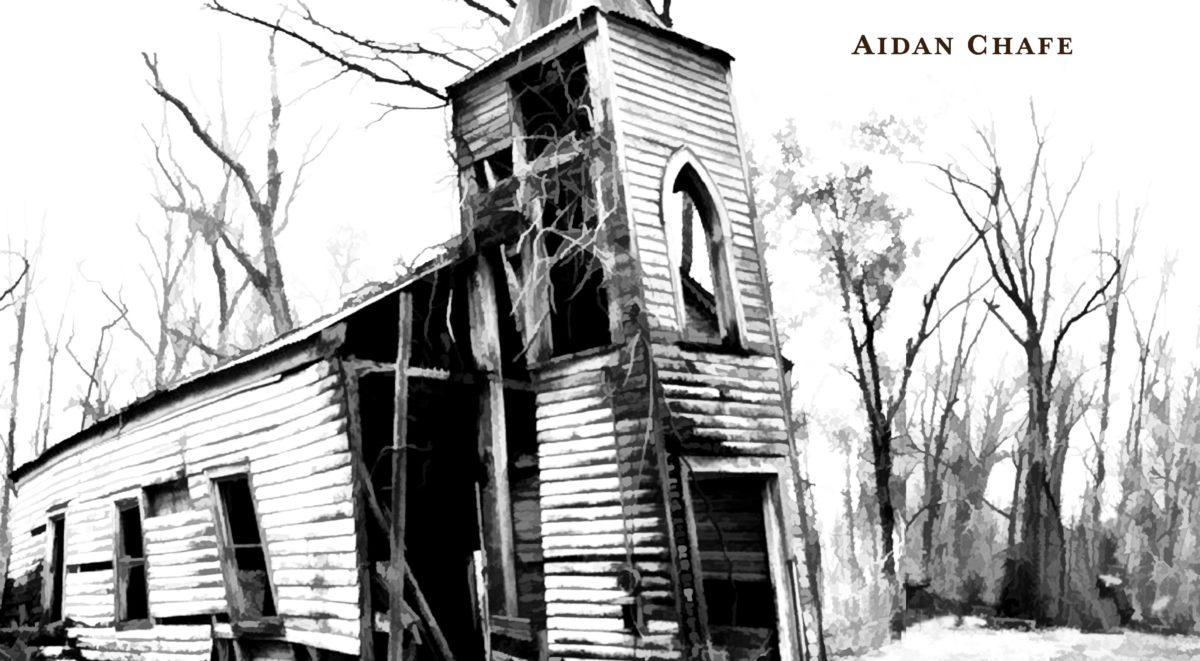

When I saw that Chafe had released a second chapbook, Right Hand Hymns (Frog Hollow Press, 2017), I was eager to read his new work. The theme of violence continues in this collection, but instead of exploring this theme in poems about hunting, woods, and wolves, Right Hand Hymns evokes a similar wildness and chaos in poems about family, religion, and mental health.

Chafe’s new chapbook is divided into two untitled sections, both of which are preceded by epigraphs. The collection’s endmatter indicates that the first–“No one has ever seen God, but the one and only Son, who is himself God”–comes from the Gospel according to John (1:18). The epigraph is an apt one, as the poems in the first section suggest a link between religion (specifically, Catholicism) and the nuclear family through recurring incarnations of the father figure, from God to the patriarch Abraham, then to the speaker’s own father. The first poem, “Why God is a Father,” centres violence as a characteristic trait of this paternal archetype. Imagining a woman’s experience of pregnancy, the speaker comments wryly.

Only a man can cause

so much pain for a woman and call it a gift.

Only a man can take away so much light

and provide none in return. (ll. 13-16)

The poems in this section take the form of short, narrative lyrics. They bring attention to the ordinary in the mythic and the grand, as well as the mythic and the grand in the ordinary. The poem “Abraham” presents a guilty father figure, a modernized mirror of the biblical patriarch who almost sacrificed his son Isaac because of God’s orders:

A whole man becomes bloated

by circumstance. The house grows old with his guilt.

Barn swallowed up by its wood. Chapel rotted

from faulty foundation. Crows oversee the coffin. (ll. 2-5)

Here the associations that come with the title “Abraham” are undercut by the banal ruin of the man in the poem. Conversely, the speaker of the following poem, “Thetis,” evokes his father in language that suggests a mythological character:

My father, greatest swimmer,

swam in the ocean of grandma’s

womb for nine months before opening

his eyes to the sun. (ll. 1-4)

The epigraph that begins the chapbook’s second section is taken from “The Depressed Person,” a short story by David Foster Wallace: “Describing the emotional pain itself, the depressed person hoped at least to be able to express something of its context—its shape and texture.” This section also contains lyric poems, though they are decidedly less structured around narrative than the preceding pieces. The first, “Chief Broom,” marks a shift in both content and form, going so far as to eschew conventions of capitalization and punctuation:

i obfuscate dilemmas

self-medicate trauma

build egos

burn them down

rebuild burn repeat (ll. 1-5)

This fragmented voice is more experimental in form than the poems that follow, though mental illness is a recurring consideration. In “Nature’s Ward,” the pathologizing language surrounding mental health issues are used as metaphors for the untidiness of the natural world:

Fields have seasonal

mood disorders.

Forests are

post-traumatic.

All the while

beyond a window

a white coat moon

keeps busy,

diagnosing

in the dark. (ll. 7-16)

Chafe certainly has a knack for a clever, surprising line. Take, for example, the opening of “Prologue to Absolute Certainty,” a poem in which Chafe returns to the hot-tempered divinity featured in the collection’s first section. The poem proceeds by anaphora:

Because death kindly waits

sometimes God throws a tantrum.

Sometimes he tosses airplanes to the ground.

Sometimes the ocean swallows ships.

Because death kindly waits

rage frequently finds the rifle. Knives nuzzle nicely

into backs. Diminutive armies unleash the deadliest

warriors: samurai of invisible silence. (ll. 1-8)

The grandiose absurdity of a divine “tantrum” where God “tosses airplanes to the ground” is mirrored by the dark irony of human armies that rely on “samurai of invisible silence,” perhaps chemical warfare.

Similar in its despondent tone and use of anaphora is the following poem, “Unsettled,” which also stands out because of the alliteration in the middle section, made all the punchier by an accumulation of sentence fragments:

Some towns didn’t have their mouth shut.

Some towns had their head cut off.

Cocaine field. Diamond trench.

Sugarcane knife. Corporate vulture.

Crop circle. Church pew. Drug den.

Corruption of police. Confederation of flags. (ll. 3-8)

Here the speaker’s keen observation leads him to social criticism. Analytical and sardonic, this voice manifests a deep dissatisfaction with the unfairness of the world order.

As in Sharpest Tooth, Chafe slowly and skillfully establishes a feeling of unrest, decay, and discomfort in Right Hand Hymns. I look forward to seeing more from him.

Annick MacAskill’s poems and reviews have recently appeared in Prism international, Versal, The Rusty Toque, Room Magazine, and Contemporary Verse 2. Her poetry has been longlisted for the CBC’s Poetry Prize, The Fiddlehead’s Ralph Gustafson Prize, and nominated for a Pushcart. She is the author of a chapbook, Brotherly Love: Poems of Sappho and Charaxos (Frog Hollow Press, 2016), and a forthcoming full-length debut (Gaspereau Press, 2018).