Interview by Selina Boan.

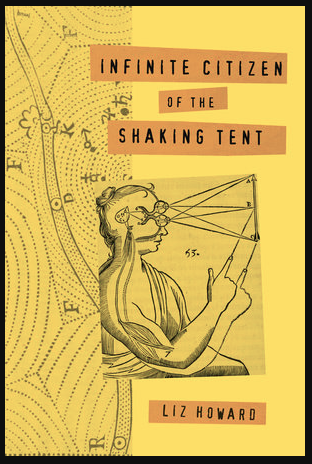

Liz Howard’s Infinite Citizen of the Shaking Tent won the 2016 Griffin Poetry Prize, the first time the prize has been awarded to a debut collection. Howard received an Honours Bachelor of Science with High Distinction from the University of Toronto, and an MFA in Creative Writing through the University of Guelph. Born and raised on Treaty 9 territory in northern Ontario, she now lives in Toronto and assists with research on the aging brain.

Howard’s work invites disruption, dreams, vulnerability. I return to her work often for its attention to texture, breath and fierce engagement with decolonization and feminism. It was an honour to correspond with Liz Howard via email and learn a little more about her favourite places to write, carpets of poppies, and the power of listening to poetry while walking.

1. What’s happening around you—either right around you or outside of where you are?

I’m sitting in my favourite place to write, the little porch outside my apartment. It faces the street so I can see people, but also, sometimes unfortunately, this renders me a kind of exhibit. People passing by on foot or in vehicles often stare at me. Sometimes they smile when I meet their gaze with a pen in my hand. Right now a dog is barking, the light is going. From the tone and prosody of his voice I can sense that my neighbour is doing business with a woman in a white car but I am either too polite or disinterested (more likely) to properly eavesdrop. Another neighbour is arriving home pushing a crying toddler in a red stroller. Every sort of dog is being walked. People are drowning in floods in Houston and India and others are dying in that way too and in others elsewhere from the site where I am now seated. Back home in northern Ontario the blueberries are at their ripest. Too many children are contemplating suicide. In the “larger universe”, to our current knowledge, all bodies are flying apart from each other at an accelerating rate.

2. Why do you live where you live?

Relatively inexpensive rent, no small matter in Toronto. My partner and I are both writers with part-time day jobs. A friend of ours we met through the MFA program was moving and put in a good word for us. It’s in the west end of the city so was much closer than my last residence to campus (Guelph-Humber in west North York). It’s within walking distance to parks and Lake Ontario. It is “safe” but also strange here, for me. It’s a very privileged (and white) neighbourhood. I have a sense of passing but only liminally. I wonder is that a part of the reason why people stare? Once an intoxicated or otherwise unwell young man came up to me while I was outside writing and negged me by saying that I was living in a “ramshackle Baltimore building” (read: his only real engagement with the notion of poverty was via The Wire) and that I should come over to his nice house down the street. The building I live in is a bit of an eyesore but it is affordable and it is my home. I grew up very poor in a small, isolated town so having a place of my own in Toronto is a victory. I don’t require a surgically designed condo.

Something that always strikes me about this neighbourhood though is that people leave out toys, plastic trucks and cars and houses and the like, outside in the parks and I never see any sign of theft or vandalism. This is so outside my experience that I feel somehow marked by it in my perplexity. That I now live in a place where there is no need or inclination to steal or lash out. Who are these people who have so much that they can just leave out toys for anyone?

When I was a little girl I used to fantasize about having one of those plastic houses but my mom couldn’t afford anything like that. The kind with a little kitchen and if I had one I’d picture taping a magazine photo of the sea to the kitchen window above the sink and stare out into it as I pretended to wash dishes, stare out into an anonymous sea that would become my sea. And out front the house I’d pin a bunch of Remembrance Day poppies that had fallen from peoples coats onto the street, I’d gather them and pin them into the carpet so that when I looked out my little front door I’d see a field of flowers. When I had this fantasy my mom and I were living in the dark, black slag rock, acid rain days of Sudbury, Ontario. Perhaps now, in this neighbourhood, I’m living a version of that fantasy.

3. What are you looking forward to this week?

The intense REM rebound induced dreaming that comes during weekend sleep after the insomnia of work days. Also hanging out with other writer friends. The way good friendships make you feel at once held and hoisted.

4. Do you have a favourite word?

I really like the word “simultaneously”. I think Kathy Acker uses it a few times on her poetry album Redoing Childhood, which I’ve listened to a hundred times and one utterance tends to loop around in my brain like an ear worm. The word “simultaneously” etches a kind of mountain range shape in fiery orange in my mind’s eye. I can’t think of any word I dislike in-and-of-itself, forsaking connotation. I know “moist” is often an abhorred word. It makes me think of cake which I like just fine.

5. What advice would you give an emerging writer?

There is the usual advice of reading broadly, deeply, voraciously. Going in the direction of one’s obsessions. Developing a “practice”, setting a writing schedule, getting out or online to engage with community, all of this is helpful. What really helped me was memorizing some of my favourite poems and to also write close readings of them (as I experienced them as I had no formal training). I keep a notebook and bring it everywhere with me. I would download readings by poets I admired (Pennsound is an invaluable resource) and put them on my iPod. I listen and re-listen to these recordings incessantly while walking around Toronto. I found that being in motion while listening helped to ingrain the metre/prosody of works I adored and this translated to my own composition.

6. What’s one risk you’re glad you took?

Completing an MFA in Creative Writing. This may not seem like so big a risk but having grownup disadvantaged this was not a pursuit I took on lightly. I had completed a degree in experimental psychology and was employed full time as the manager of aging and cognition laboratory. I was very fortunate to have found a job in my field but after a number of years it became clear to me that I was not going to further my career my completing a psychology PhD. I could never get ahead on my student loan payments. I was trapped in debt and very depressed. At the same time I was also writing and publishing and publishers where beginning to express interest in seeing a manuscript that didn’t exist yet. I knew the only way I would produce enough work was if I had the structure and support of a writing program. I told myself that I could make it work financially by going down to part-time in the lab and working a few nights in a bar. This plan failed, devastatingly so. Fortunately I was awarded a last minute SSHRC (graduate scholarship) and it financed the time off I needed to complete my creative thesis. The thesis became the core of the book McClelland and Stewart agreed to publish. It’s been a wild ride ever since.