Review by ALHS

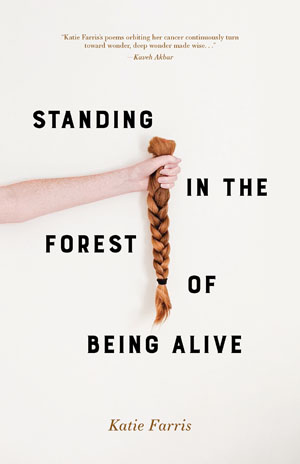

Katie Farris’s debut collection, Standing in the Forest of Being Alive, is frank and vivacious, weaving out of the complexity of life an argument for life. Standing in the Forest of Being Alive is a memoir-in-poems in which its narrator navigates breast cancer, a pandemic, and political upheaval. “Why write love poetry in a burning world?” Farris asks in the opening poem and her answer is both proem and refrain, resolute and pensive:

To train myself to find, in the midst of hell

what isn’t hell.

(“Why Write Love Poetry in a Burning World”)

In this collection, Farris’s love poems pursue wonder to the point of hilarity: “What vertical absurdity! / What upright madness!” (“Outside Atlanta Cancer Care”). Some unfold as a single conditional sentence that forgets its own conditionality and breaks out into a search for love. In “If Marriage,” the speaker sweetens a cautious conditional with the certainty of a premise:

If marriage

is a series

of increasing

intimacies… I

would still beg

your forgiveness

for asking

your assistance

unwinding that pale hair

from my hemorrhoid.

She also poses lingering questions in generous enjambment: “I am trying to be a love poet though I cannot escape / America it’s as if I’m married to / America and no one stood to object” (“The Invention of America”). Her poetry asks: where is there space for erotic love? Eros wanders within the body, sometimes it wanders without. Sometimes it is a chair, “perfect for lovemaking” (“Rachel’s Chair”).

So often eros finds expression in the achingly terrestrial. Distances and thresholds offer themselves readily to love poetry. In “I had been hungry, all the Years,” Emily Dickinson wrote, “so I found / That Hunger—was a way / Of Persons outside Windows— / The Entering—takes away—” Farris holds Dickinson close, writing, “Today I placed / your collected poems / over my breast, my heart” (“Emiloma: A Riddle & an Answer”). Perhaps eros is an appreciation for the fault after the ground beneath us has trembled. Eros must shake us.

That eros must shake us, must set us aquiver is both an observation and a demand within these love poems. In Farris’s voice, tender and catching with laughter, this is, foremost, a demand of the self that wants to pour forth beyond itself. In eros, the self wishes to encompass something vast. In “Outside Atlanta Cancer Care,” Farris describes this desire as material, as a body imitating a tree: “for if you long hard enough, / do you not find fruit / in your palms?” A self grows toward the recipient of its wonder, and for Farris, this wonder is trenchant, standing to offer an origin hypothesis for human beings. Here, the erotic hovers, as conceived by Audre Lorde in Sister Outsider, “a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings.” Farris navigates her landscape with the gentle unsettling of where the world ends and the self begins, gentle as the parenthetical hinge within the love poem:

(Why do love poems attract birds as sure as seed or worm or nectar?)

(“In the Shadow of This Valley”)

To essay toward an answer, something about the bird’s smallness. When caged, a bird is a heart, a self, beating steadily. If released, it flies from one poem to the next, carrying messages addressed to anyone. In the case of Farris’s poems, they are addressed to multiple different figures.

Address bridges oneness and otherness. When a poem addresses a certain figure, it mediates, and like eros, measures the space between the self and what the self reaches toward. Farris plays with this notion in “The Invention of America.” “As an anti-capitalist act, I reject your hierarchies of worth, America—” Farris writes in a clear statement of poetics, “All things are erotic.” Farris unfurls the capacious eros of address, weaving her addressees into intimate vocatives. Here, the vocative holds America cursorily in its gaze before naming the enduring cockroach — “O cockroach, / smooth as a lozenge, glossy / as hard candy, antennae / clever as spun / sugar, come / into my mouth.” This is no comparative device. This is a dance of invocation and imperative, a sense of rhyme encompassing the entirety of being. Elsewhere, Farris writes of cancer, “I name you “cactus,” / carcinoma be damned” (“Tell It Slant”).

In Farris’s vocatives, the use of address carries the sincerity of an apology or the hilarity of dedication. In “Quid Pro Quo: A Dedication,” Farris writes, “So here’s / your god- / damn / poem.” Indeed, the vocative is volatic and in continuous turn. In orienting herself away from hell, Farris sets course towards wonder, towards an insistence on life, and comes to the eros of address that moors gently in the self. In searing wonder, Farris writes,

[…] And whom can I tell how much I want to live? I want to live

(“Woman with Amputated Breast Awaits PET Scan Results”)

ALHS is a poet and critic. She lives and writes on the unceded land of the Lək̓wəŋən peoples.