Summer Writing Prompt: Week 4

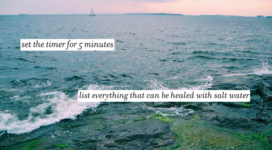

No, you may not use ‘a sore throat’ in your list. If you’re stumped, keep rewriting the last word until something comes.

No, you may not use ‘a sore throat’ in your list. If you’re stumped, keep rewriting the last word until something comes.

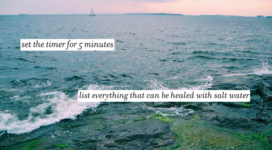

Suggestions: – The lyrics from that early 2000s quasi-alternative-rock song your brother blasted from behind his bedroom door when you were both growing up. – The excerpt from that rap song that you usually just mumble. – That song you...

We are so happy to announce that our merchandise is finally available on our store. We love our totes bags with zippers. They are stunning and have zippers! The notebooks come as a set and we love them too! Just imagine...

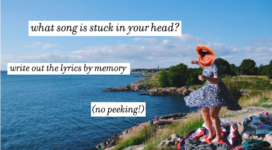

Olga Holin sat down with our PRISM international Creative Non-fiction Contest judge Jonathan Kemp and spoke to him about his writings and what he is looking for amongst the entries.

We are happy to announce that our annual PRISM international Non-Fiction Contest is now open for submissions. We are absolutely delighted to introduce our judge from across the pond: Jonathan Kemp! Jonathan Kemp’s debut novel London Triptych (Myriad, 2010) was acclaimed...

Our “BAD” themed issue will be on stands soon, and includes work by some of Canada’s most talented and thought-provoking emerging writers. This issue is an invitation to reconsider our biases and values, and to test the limits of...

Interview by Kyla Jamieson

Emerging writer Marc Perez’s story “Dog Food” appears in our “BAD” issue. Of his story, Perez says, “I once had a dog, and I named her Bruce. The story is a lament for her.” For this issue, we sought work that took us to true places along difficult or unexpected paths; “Dog Food” is one such story. In it, a boy witnesses violence he’s helpless against, and is denied understanding in the aftermath. His pain is real, but nobody sees or acknowledges it; where can it go but forwards, into his future?

Marc Perez immigrated to Canada from the Philippines and now lives on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. Perez has been working in the nonprofit industry for the past five years; in addition to this work he is currently participating in Writing Lives, a project in which writers collaborate with Holocaust survivors to write their memoirs. Read on for Perez’s thoughts on identity and home, privilege and marginalization, and the best time to write—while asleep and dreaming.

Heart Berries

Terese Marie Mailhot

Doubleday Canada

Review by Cody Caetano

Often when I’m reading memoir, I’ll remember a quote from a misguided Neil Genzlinger, who penned “The Problem With Memoirs” for The New York Times in 2011: “There was a time when you had to earn the right to draft a memoir… Sure, [Amazon] has authors who would be memoir-eligible under the old rules. But they are lost in a sea of people you’ve never heard of” (italics mine). It is important to note that marginalized memoirists, especially early-career Indigenous women, Two-Spirit, and queer folks, have fraught histories with Genzlinger-types, their “old rules” and antiquated tastes that mar the merit of writing, publishing, and participating in the predominantly white spaces of the literary world. And then along comes Terese Marie Mailhot, a Salish First Nation woman from Seabird Island Indian Reservation with the assertion that memoir “functions as something vulnerable in a sea of posturing” (137). And it is in vulnerability that Mailhot effectively rejects the moth-eaten straightjacket that would otherwise restrict the inventive, decolonial confession of Heart Berries.

Continue reading Decolonial Confession: A Review of Terese Marie Mailhot’s Heart Berries

Interview by Matthew Kok

Beni Xiao is a nanny and writer based in Vancouver, BC. They are tired all the time, so they would appreciate if you’d let them sleep. Bad Egg, Beni’s new chapbook, is full of quiet, important things. There is a garden of variety in these poems, and the chapbook is drawn together by the strength of Beni’s voice. The effect is a lot like having a small bug perched in your ear, joking, encouraging, asking. They are willing to go with you into storms. They will not lie and tell you your impact on the world is going to be anything other than what it is. They will tell you about the hard, strong thing we all need to be sometimes, and as they describe it you may believe it is you—it may depend on the day, or whose limbs you’ve found crossed over your own, but the bug will say it for you if you can’t. There is a whole world of people who will speak around the important things rather than to them, or ignore the strange and the wonderful, but none of them are in this chapbook. You should start listening to Beni Xiao—I promise it will be worth it.